Watching dog mothers take care of their pups continues to fascinate me, after the extensive research my team conducted in the 1980s. The large populations of village dogs in Africa and Thailand, where I spent and spend much time, provide me with plenty of opportunities to continue doing it. Village dogs are domestic dogs, not wild. Often classified as strays by the inept, ignorant eye of the western tourist, these dogs perform an essential task in their communities of humans and their domestic animals.

Maternal behavior is behavior shown by a mother toward her offspring. In most species, she is the one taking primary care of the youngsters, canines being no exception. Natural selection favored the evolution of this particular behavior in females.

In wild canids, although the female watches over the puppies, the father (also called the alpha male or pack leader) and other adults come interested in the feeding and raising of the pups when they emerge from the den. In the surveys my team did in the 1980s, our dogs showed the same pattern in a domestic set-up.

Thus, maternal behavior is identical in wild canids and domestic dogs. After birth, the mother dries the puppies, keeps them warm, feeds them and licks them clean. Hormonal processes control maternal behavior right after birth, and problems may occur if the female gives birth too early. On the other hand, pseudo-pregnancy causes females to undergo hormonal changes, which may elicit maternal behavior in various degrees. Maternal behavior appears to be self-reinforcing. Studies show that the levels of dopamine increase in the nucleus accumbens (a region of the brain) when a female displays maternal behavior.

When the puppies become older, the mother educates them. She gives them the first lessons in dog language at the time weaning occurs. Growling, snarling, and pacifying behaviors are inborn, but the pups need to learn their function.

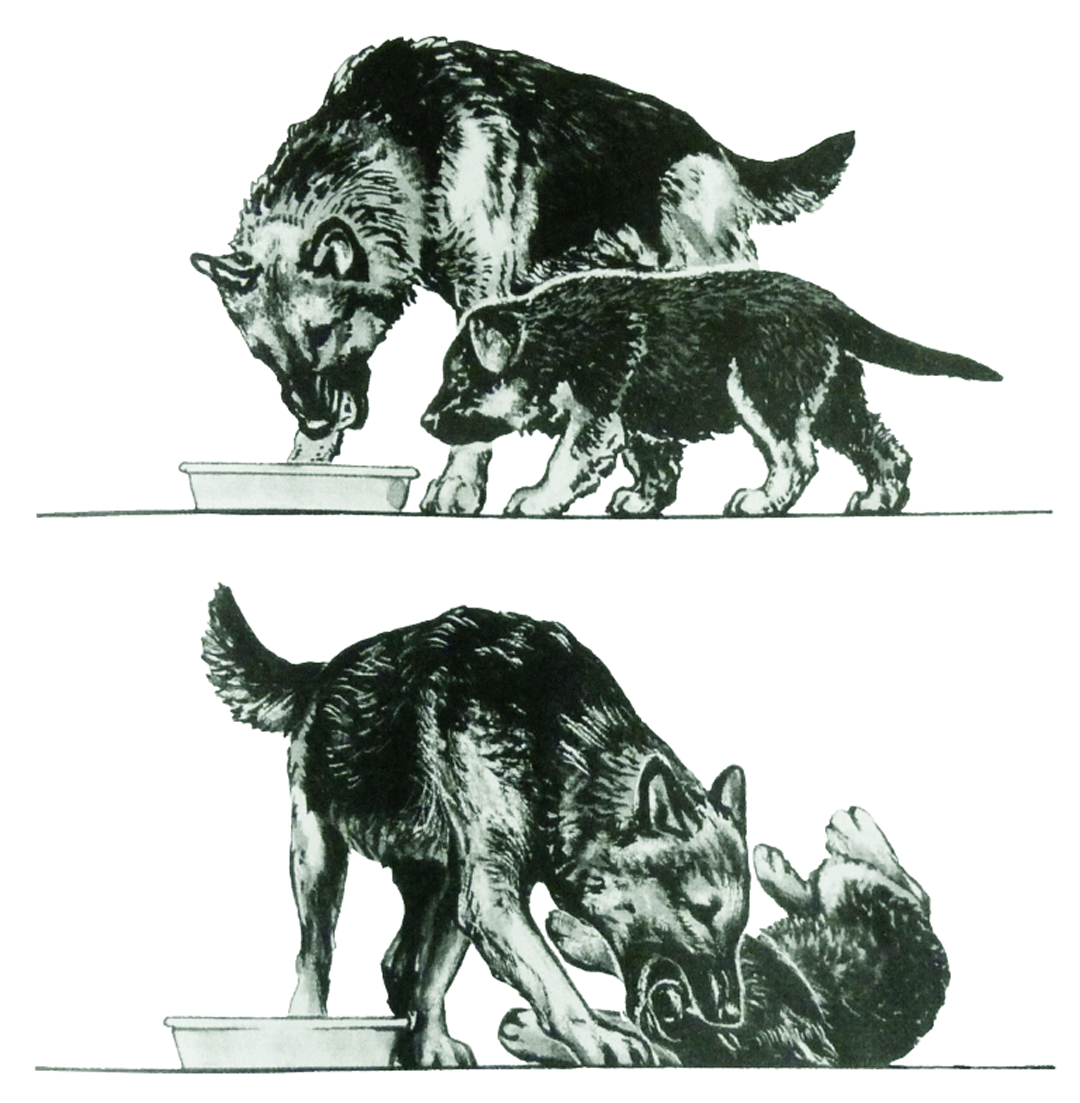

When the puppies become older, the mother begins to educate them. She gives them the first lessons in dog language about the time weaning begins (Illustration by Alice Rasmussen from “Dog Language” by Roger Abrantes).

The canine mother has four main tasks: (1) to feed the puppies, first with her milk, then by regurgitation, (2) to keep them clean and warm, especially when they are young, (3) to protect them and the den (with the help of the pack), and (4) to educate them.

A good canine mother is patient and diligent. Dog owners often misunderstand the mother’s more robust educational methods. She may growl at them and even seem to attack them, but she never harms them. Muzzle grasping is relatively common (see illustrations).

Without the mother’s intervention, the pups would never become capable social animals and would not function in a pack (a group of wild dogs living together is, in English, a pack). When the puppies are about 8-10 weeks old, the mother seems to lose some of her earlier interest in them. In normal circumstances, the rest of the pack takes over the continuing education of the pups, their social integration in the group (which mainly comprises relatives), and their protection.

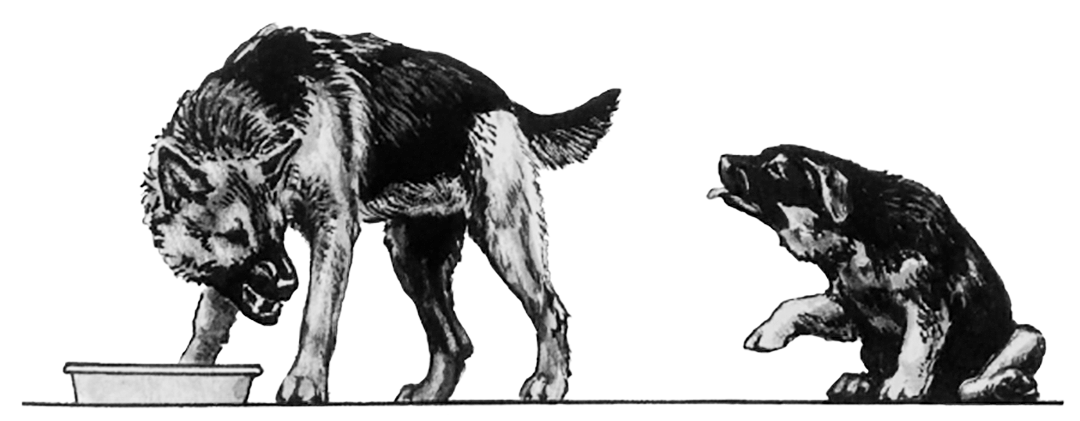

The puppies’ most common responses to their mothers ‘no’ or insistence in overturning them are the vacuum licking and the twist behavior. The puppies learn it quickly. These are vital lessons to develop healthy social behavior and thrive in a group: they must understand that sometimes one gets one’s way and sometimes one doesn’t—and to get the best out of both is what social life is all about.

The function of the twist behavior is to pacify an opponent. As always, behavior happens by chance (or reflex), and if it (the phenotype) proves to have a beneficial function, it will spread in the population, transmitted from one generation to the next (via its genotype). The twist’s origin goes back to the canine female’s typical maternal behavior of overturning her puppy by pressing her nose against its groin, forcing one of the puppy’s hind legs to the side. The puppy will then fall on its back, and the mother will lick its belly and genital area, facilitating the puppy’s urination and defecation. At first, the puppy seems to find it an unpleasant experience that becomes pleasurable once it rests on its back and its mother’s licking achieves its function (see illustration).

Dog owners sometimes report problems, e.g., that the mother has no interest in her puppies or is too violent towards them. Both are alarm signals we should not dismiss. Both are strategies that would not spread into a population of social animals should we not intervene. Our selective breeding is the primary cause of this issue. We select for beauty and utility while nature selects for overall fitness, including adequate maternal behavior. Our lack of understanding of the mother’s needs during and after birth often results in the female showing stress, insecurity, or aggressive behavior.

After learning ‘no’ in dog language (see the previous illustration), puppies quickly learn how to deal with it (Illustration by Alice Rasmussen from “Dog Language” by Roger Abrantes).

The maternal effect is the mother’s influence on her pups. It can have such an impact on particular behaviors it may overshadow the role of genetics. For example, observations show that a female showing too nervous or fearful reactions toward sounds may prompt her puppies into developing sound phobias beyond what we would expect given their specific genotype. Therefore, it is difficult, if not impossible, for researchers to assess the hereditary coefficient for particular traits.

Bottom-line: Do not breed females you suspect will not show adequate maternal behavior and do not disturb a female with pups. A good canine mother knows better than you, what’s best for her pups.

References

Abrantes, R. (1997). The Evolution of Canine Social Behavior. Wakan Tanka Publishers.

Abrantes, R. (1997). Dog Language. Wakan Tanka Publishers.

Bray, E.E., Sammel, M.D., Cheney, D.L., Serpell, J.A., Seyfarth, R.M. (2017). Maternal style and guide dog success. — Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Aug 2017, 114 (34) 9128-9133; DOI:10.1073/pnas.1704303114.

Coppinger, R. and Coppinger, L. (2001). Dogs: a Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution. Scribner.

Darwin, C. 1872. The Expressions of the Emotions in Man and Animals. John Murray (the original edition).

Fox, M.W. (1971). Behaviour of wolves dogs and related canids. Dogwise Publishing, Wenatchee, WA.

Foyer, P., Wilsson, E. & Jensen, P. (2016). Levels of maternal care in dogs affect adult offspring temperament. — Sci Rep 6, 19253 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep19253.

Freedman, D.G., King, J.A. & Elliot, O. (1961). Critical period in the social development of dogs. Science 133: 1016-1017.

Klinghammer, E. & Goodmann, P.A. (1987). Socialization and management of wolves in captivity. — In: Man and wolf: advances, issues, and problems in captive wolf research (Frank, H., ed.). Kluwer, Dordrecht, p. 31-61.

Lazarowski, L., Katz, J.S. (2018). Mothering matters: Maternal style predicts puppies’ future performance. — Learn Behav 46, 327–328 (2018). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13420-017-0308-8.

Lezama-García, K., Mariti, C., Mota-Rojas, D., Martínez-Burnes, J., Barrios-García, H. & Gazzano, A. (2019). Maternal behaviour in domestic dogs. International Journal of Veterinary Science and Medicine, 7:1, 20-30, DOI: 10.1080/23144599.2019.1641899.

Lopez, Barry H. (1978). Of Wolves and Men. J. M. Dent and Sons Limited.

Mech, L. D. (1970). The wolf: the ecology and behavior of an endangered species. Doubleday Publishing Co., New York.

Mech, L. David (1981). The Wolf: The Ecology and Behaviour of an Endangered Species. University of Minnesota Press.

Mech, L. D. (1988). The arctic wolf: living with the pack. Voyageur Press, Stillwater, Minn.

Mech. L. D. and Boitani, L. (2003). Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. University of Chicago Press.

Pal, S.K. (2005). Parental care in free-ranging dogs, Canis familiaris. — Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 90: 31-47.

Scott, J.P. (1958). Critical periods in the development of social behavior in puppies. — Psychosom. Med. 20: 42-54.

Scott, J. P. and Fuller, J. L. (1998). Genetics and the Social Behavior of the Dog. University of Chicago Press.

Slabbert, J.M. & Rasa, O.A. (1993). The effect of early separation from the mother on pups in bonding to humans and pup health. — J. S. Afr. Vet. Ass. 64: 4-8.

Wilsson, E. (1984). The social interaction between mother and offspring during weaning in German shepherd dogs: individual differences between mothers and their effects on offspring. — Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 13: 101-112.

Wilsson, E. (2016). Nature and nurture—how different conditions affect the behavior of dogs. — J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 16: 45-52.

Woolpy, J.H. & Ginsburg, B.E. (1967). Wolf socialization: a study of temperament in a wild social species. — Am. Zool. 7: 357-363.

Zimen, E. (1975). Social dynamics of the wolf pack. In The wild canids: their systematics, behavioral ecology and evolution. Edited by M. W. Fox. Van Nostrand Reinhold Co., New York. pp. 336-368.

Zimen, E. (1982). A wolf pack sociogram. In Wolves of the world. Edited by F. H. Harrington, and P. C. Paquet. Noyes Publishers, Park Ridge, NJ.

Featured image: English Cocker Spaniel mother and pup (photo by Cynoclub).

Feel free to leave a comment, pose a question, or share your thoughts. Your opinion matters. I will reply to all messages and answer all questions to the best of my ability.