Stating a fact does not oblige me to adopt any particular moral stance. What science teaches me about a fact does not impose any moral stance on me or how I feel about it. It may impact my decision, but my ethical decision is ultimately independent of scientific truth. Science tells me men and women are biologically different in some aspects, but it does not say whether or not they should be treated equally in the eyes of the law. Science tells me that evolution is a consequence of the algorithm “the survival of the fittest,” not whether or not I should help those that find it difficult to fit into their environment. Science informs me of the pros and cons of consuming animal products, but it does not tell me whether being a vegetarian is morally right or wrong.

You are standing on shifting sands if you believe it is safest to base your moral judgments on facts (and probably committing a fallacious appeal to nature).

Cutting off parts of the body of an animal for our vanity is and will always be wrong for me independently of what science may discover.

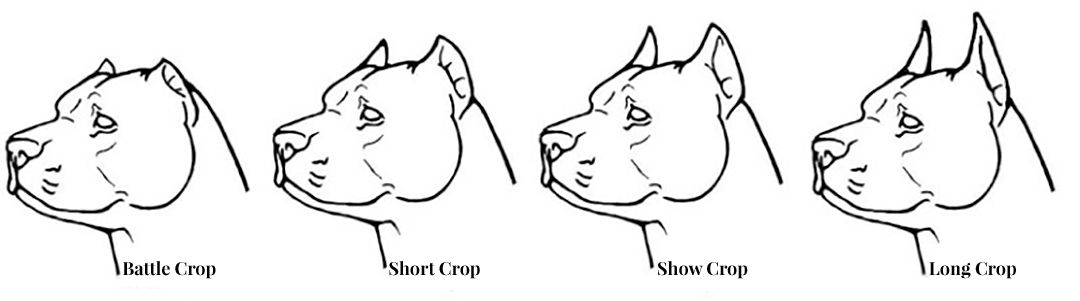

Let’s say someone asks you, “Why do you believe tail docking to be wrong?” You will get into trouble if you respond, “Because it prevents the dog from fully communicating, as dogs use their tails to communicate.” Say again, the same person asks you, “Why do you believe ear cropping to be wrong?” You cannot respond, “Because it prevents the dog from communicating efficiently as dogs use their ears to communicate,” as dogs with upright ears may express themselves more and in more easily recognizable ways than those with drop ears (although no study has proven that cropped ears are better for communicating than uncropped).

That is the unseen danger we face when we rely on facts to support our moral claims: we risk immediately encountering illogical reasoning. Even if it seems like some people are not bothered by that, it undoubtedly concerns others, including myself, who have some intellectual integrity.

You could avoid this problem by answering, “Because I don’t like to cut off parts of an animal.” That would do it because nobody can argue with what you like or don’t like. Even if you neuter your male dog (which means cutting off the testicles of the animal), you are still off the hook because you can say, “I did it, and I don’t like it.” There is no logical contradiction in doing something without liking it. It is only logically contradictory if you infer the premise, “We only do what we like.” “I don’t like diets, and I’m on a diet” is perfectly all-right. You may have a goal that requires you to do things you don’t like.

Another aspect of this hidden danger of basing your morality on facts is that if science uncovers some new fact relevant to your morality, you’ll be forced to change it. One moment right, the next wrong; this is true of scientific theory but not always of morality.

For example, if I use the seemingly good argument, “It is wrong to inflict unnecessary pain and distress on any living creature, independently of species,” my morality is at the mercy of scientific discovery.

Thus, the only way I can make my moral rule stick appears to be the subjective argument: “for me, it is wrong to cut off parts of an animal’s body because I don’t like it”. And if science uncovers some painless, undistressing procedures for docking and cropping, then so be it. I still find it objectionable and won’t comply. Period.

References

Copi, I. (2013). Introduction to Logic. Routledge, 14th ed. ISBN-10: 1292024828. ISBN-13: 978-1292024820.

Hume, D. (1739). A Treatise of Human Nature. John Noon, London. ISBN: 0-7607-7172-3.

Marchetti, G. and Marchetti S. (2917). Facts and Values—The Ethics and Metaphysics of Normativity. Routledge. ISBN: 9781138615410.

Moore, G.E. (1903). Principia Ethica. Cambridge University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/UPO9781844653614.003.

Resnik, D.B. (1998). The Ethics of Science: An Introduction (Philosophical Issues in Science. Routledge. ISBN-10: 0415166985. ISBN-13: 978-0415166980.

Singer, P. (2011). Practical Ethics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN-10: 0521707684. ISBN-13: 978-0521707688.

Featured image: Facts versus Ethics. Composition by Roger Abrantes (photos by unknown).

Feel free to leave a comment, pose a question, or share your thoughts. Your opinion matters. I will reply to all messages and answer all questions to the best of my ability.